works

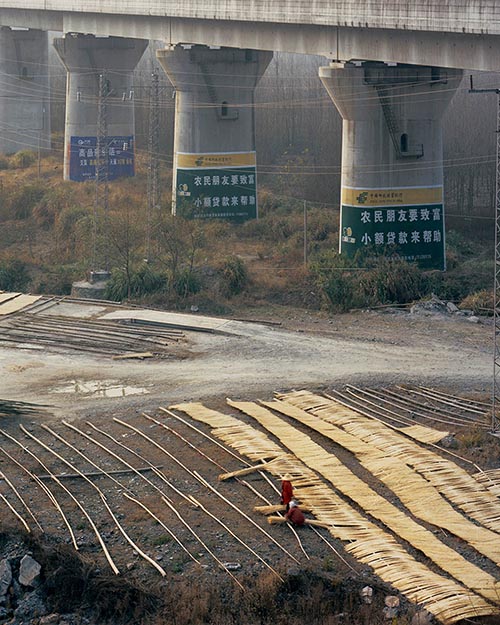

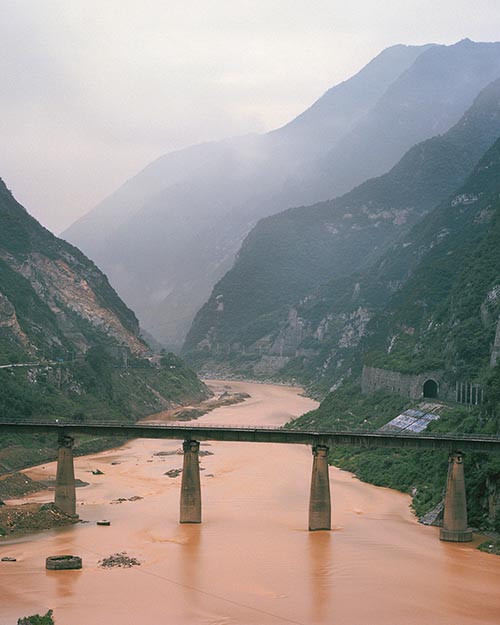

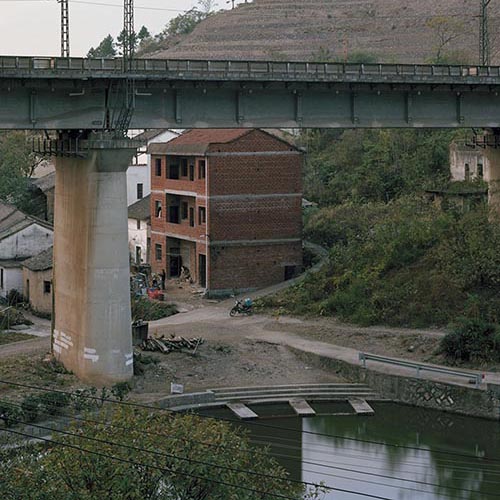

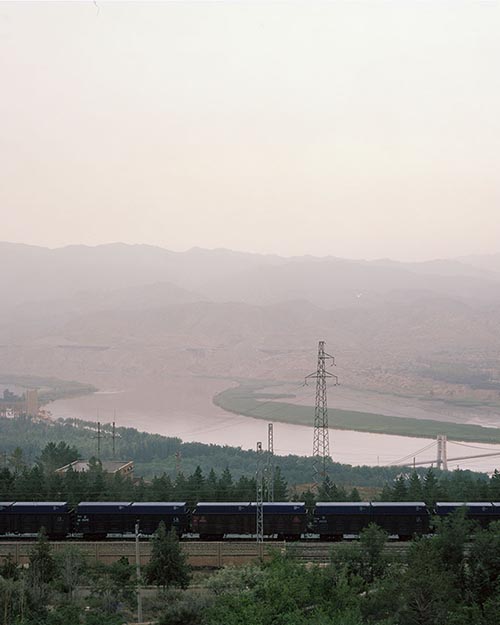

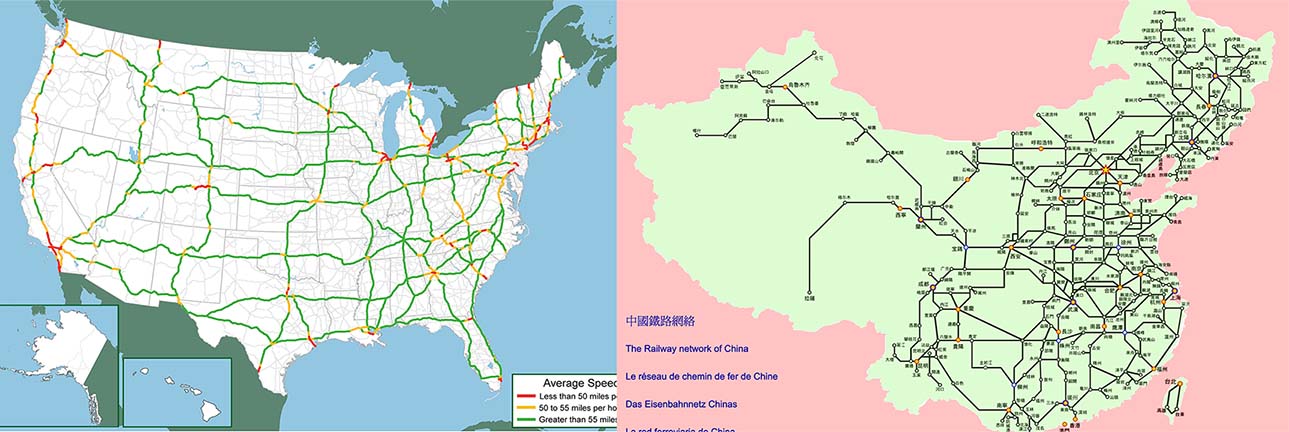

The Great Eastern looks at China against the backdrop of high speed rail expansion. This sweeping infrastructure project is a domestic strand of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) or One Belt One Road Initiative or New Silk Road or any number of other designations it’s had so far. Whatever the branding, it is China’s massive development strategy to promote goodwill, indebtedness and habitual compliance around the world. This sprawling high-speed network is the aspect Chinese people will experience most directly. With passengers travelling up to 350 km/h on 38,000 km of new tracks, the existing railways can be reserved for freight. China’s interior shipping capacity will effectively double over this course of this three-decade project. In the whole of human history only the US Interstate Highway System has been more extensive and expensive; approximately 77,540 km of roadway rolled out piecemeal between 1956 and 1992.

These metrics of scope and cost are only somewhat compelling in and of themselves. What’s more fascinating is the civilizational engineering each scheme facilitates. While the United States and China are markedly different societies, they are also the planet’s third and fourth largest nations and both are bent on achieving degrees of dominance. In this sense they’re flip sides of the same coin. Whether the BRI is being compared to America’s Marshall Plan or painstakingly disentangled from that analogy, the two campaigns have come to define each other. The Interstate Highways and China’s high-speed railways are domestic expressions of this global ambition. China is now being transformed in much the same way the US was re-invented throughout the 20th century. Before Seattle and Dallas and even Anchorage, Alaska were joined by serviceable roads, the US was a profoundly different place. It was quainter. McCarthyism, Jim Crow and a legacy of indigenous genocides notwithstanding, there’s something charming about a patchwork nation of country roads, city streets and barely paved byways. I imagine eating fried chicken in the South and seafood on the coasts. A range of local dialects would have provided directions and lodging and gas, and there would have been a lot of stopping to chat. Travel was slow, confusing and weather dependent.

The highways’ funding bill passed in 1956. It took five years for the phrase ”America’s love affair with the automobile” to be coined. There were four McDonald’s restaurants at the outset and a thousand twelve years later. The Interstates carried the ideology of American exceptionalism throughout the nation and beyond. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 notions of global communism were also rendered moot. Within months the world’s then largest McDonald’s opened in Beijing, the largest Communist capital. As of 2016 McDonald’s had 36,899 franchises in 120 countries serving 68 million meals each day. Regardless of social costs, benefits and ostensibly neutral markers, the age of the Interstates has formed our world. Google Books’ Ngram Viewer indicates that "consumer” and “citizen” appeared in print with similar frequency in 1956. Today “consumer” is published three times as often.

It’s unclear exactly how China’s advance will play out over time. Its present is suffused with such ambivalence. Despite decades of economic growth and burgeoning cultural confidence, the 20th century was grim for the Chinese. The Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution left huge swaths of the country dysfunctional and languishing out of time. Another superlative “the largest migration in human history” describes more than 200 million rural migrants fleeing to low-status jobs in special economic zones and megacities in recent decades. It’s a precarious imbalance. Boomtowns suffer overcrowding, pollution, and discrepant resources. 35% of provincial labour remains mired in agriculture, and much of that is at subsistence levels. It’s down from a staggering 60% in the early 2000s, but Western economies haven’t been structured like that for centuries. For context, the US and Europe employ 2.5% and 4% of their respective labour forces in agriculture. America became predominantly urban in 1920; that didn’t happen in China until 2012. In a sense China’s high-speed rail network can be likened to a time machine. Connecting its myriad backwaters to robust coastal cities and to one another may well propel them into the future. As the armature for countless regional and local ventures the infrastructure could indeed reduce, then stem, and optimally reverse the tide of migrants evacuating China's interior. Redistributing some portion of a fifth of all humanity can be discussed in terms of demographics or logistics or incentives, but as sea levels inevitably rise the urging of people inland may come to be seen as simply prescient.

News